An Opening Door

By Rev. Canon Susanna Gunner England 15.08.2024

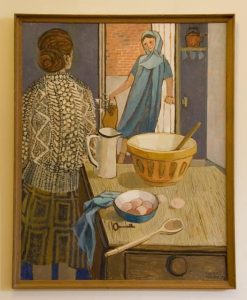

Image by Claudia Williams

One afternoon last summer, on retreat at St Beuno’s in Wales, I took myself to a little sitting room to do some reading. But my eye was immediately drawn from the page on my lap to a painting hanging above the fireplace. I was alone in the room so I wriggled a chair right in front of it and looked and looked…

One afternoon last summer, on retreat at St Beuno’s in Wales, I took myself to a little sitting room to do some reading. But my eye was immediately drawn from the page on my lap to a painting hanging above the fireplace. I was alone in the room so I wriggled a chair right in front of it and looked and looked…

I realised that whoever the painter was had whisked me into a moment between two first century women, a moment of monumental import (Luke 1.39-56). Mary, wearing a maternity dress in the blue of heaven, has just opened the door into Elizabeth’s homely kitchen. She is the bearer not only of divine news but also of a divine child and, desperate to share all this with her cousin, has not waited for her knock to be answered. A scarf in exactly the same blue is draped on the kitchen table. What does this signify? That Elizabeth is ready and waiting to respond to the heavenly child Mary carries? That they will soon be talking about the powerful connection they feel between the child in Mary’s womb and the one in Elizabeth’s?

Mary stands in the doorway of Elizabeth’s home with a few gleaming-white lilies in her bag and a loving smile on her face. It feels as if the painter (who I now know to be Claudia Williams b.1933) is taking us with those lilies on a journey. So often they feature when, by artists down the ages, Gabriel is depicted giving his message to Mary about her extraordinary pregnancy, classic symbols of her purity and innocent vulnerability. Williams has imagined Mary packing up the flowers and taking them with her to the hill country where Elizabeth lives, thereby reminding us of Mary’s recent encounter with the angel and creating a flowery link between Annunciation and Visitation.

But there are other links too… Just as many classic Annunciation scenes indicate the divide between earth and heaven but also that in this encounter that divide has somehow been transcended, so here in this Visitation scene, Elizabeth’s kitchen stands open to Mary who is literally on the threshold, in a liminal space pregnant with possibility, at one and the same time in and of the world and bearing its Creator.

And then there are all those geometric shapes and patterns – in the brickwork behind Mary, in the stripes on the door which she’s just opened, in the square block design of Elizabeth’s skirt and the cable patterns of her knitted jumper, in the grain of the wooden table top. Again, this geometric feature sometimes pops up in annunciation scenes. Look, for example, at Botticelli’s (1481), Eric Gill’s (c.1912) and Dinah Roe Kendall’s (2005). What might all those repeated shapes be saying? Perhaps that the Creator whose universe is suffused with the most beautiful pattern and proportion is also at the very heart of this encounter and everything to which it will lead, purposefully conceiving a new order, utterly in control. Claudia Williams brings those same ideas into Mary’s visit to Elizabeth, making the point that this moment too is an essential one in the revealing of God’s plan.

Elizabeth looks toward Mary in greeting, her age subtly indicated by her clothing and rounded shoulders. She turns from her work at the table, calmly open to the girl on her doorstep. Dare I let Mary and her child into my kitchen too? Is my blue scarf of response ready and waiting? What will leap inside me when they are near? And what is already lying within me waiting to be birthed by God?

The key lying on the table is there for a reason. It is, I think, a signal from the artist that this moment holds the secret to a very significant unlocking – not just of the meaning of those two babies in utero and to the relationship which will emerge between them, but also to an unlocking of us, when we like Elizabeth, are involuntarily stirred by the presence of Jesus.

We know it will not be easy for either of these women (both their little boys will be put to death as young men), and perhaps the small parts we ourselves might play in the unfolding of God’s beautiful pattern will be testing for us, yet the painting holds up a resilient, determined lens to expectancy, hope, newness. And those foregrounded, unmissable eggs speak not just of birth, of course, but of resurrection, of re-birth, of a divine transformative process which cannot be halted by rejection and death and loss.

SEE ALL BLOG POSTS